The Six of Cups of the tarot is an invitation to focus on cultivating a childlike sense of wonder, joy and freedom. The wisdom of this card is increasingly important in a world where suffering runs rampant and systems of domination are protected by law. Children are naturally generous, unapologetically emotional and freedom focused; We learn to embrace our childlike nature, and a more liberatory approach to life, with the Six of Cups and our inner child.

☆ ☆ ☆

When I ask my mother what I was like as a child she says without missing a beat, “serious.”

I ask her to elaborate and she continues, “you used to repeat everything I said! You loved the rules… A real goody two shoes.” I cringe, eyes down, running my hand through my hair.

“You never wanted to be held,” Mom adds, “You wanted to be up and crawling and walking and talking.”

This mostly aligns with what I can remember of my childhood. I spent my early years wishing I was grown. I used to stay up late watching Masterpiece Theater on PBS with my mom. My favorite food was smoked salmon for god’s sake. I was curious, precocious and a little pretentious. I longed for an older sister that I could turn to for advice, someone to show me the way. I even remember that I used to take my books out of my backpack on the way home from school and carry them clutched to my chest because I’d seen older kids on TV do that.

Maybe I had some level of sincere interest in adult life, but I think I associated myself with adults in an attempt to move closer to safety. I was a fearful child; The rules, and the praise I received when I followed them, provided me with a sense of comfort — something I could cling to.

When I was 8 years old, I had my palm read at a friend’s birthday party.

“You’ve got two sides to you,” The psychic told me, looking into my small outstretched palm. I was curious. What could that mean?

She continued, “One part of you is like a little boy who loves adventure! The other side is like an old lady, who loves the rules.” She grimaced. Her eyes looked a little concerned, “That old lady inside you doesn’t know how to have fun. Be more like the little boy.”

At 8 years old, I had no real interest in spirituality but the reading stuck with me. I found it difficult to take her advice, though. I spent most of my childhood acting as the old lady. I fixated on minute fears as a way to avoid larger fears of the unknown. Rules and restrictions were temporary consolation in a world that felt increasingly unpredictable. As a teenager, I tamped down on the freedom that substance and sex offered me with obsessive-compulsive rituals. I wanted control.

Then, a shift. It began as an early adult when I started working with young children.

I watched the little beings around me discover their environment through sensory play. They expressed their wants and needs without apology. They seemed to be in a constant cycle of falling down and getting back up without becoming defeated. I was inspired. I also wanted to play in the dirt and bang on things loudly and wear my shirt inside out “just because.” The little boy inside of me was eager to play.

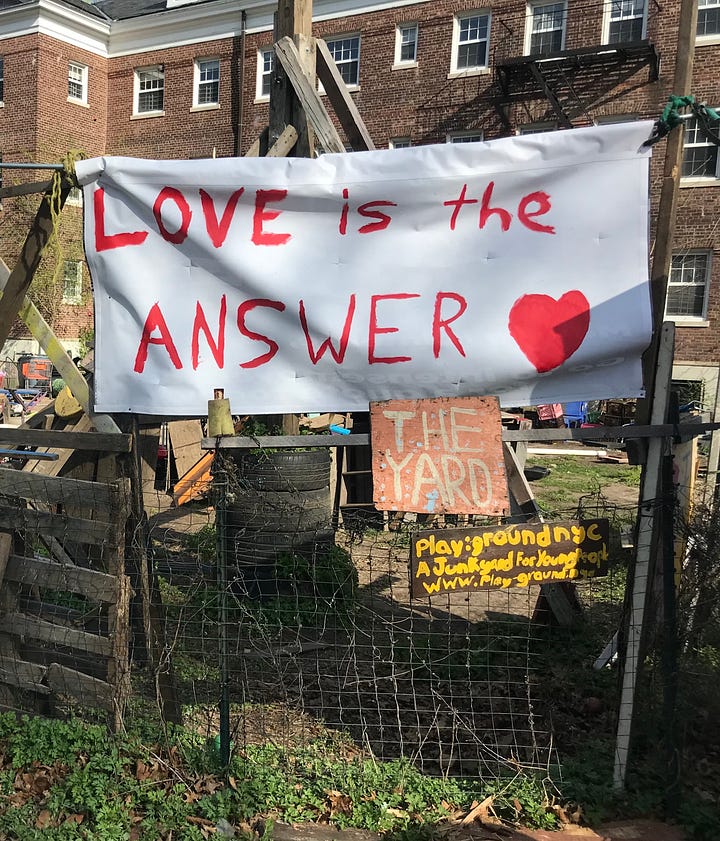

Discovering playwork has shaped how I work with children and my own inner child. I was first introduced to the concept the summer after college when I became a playworker at the Ithaca Children’s Garden. At the Children’s Garden, I put flowers in my hair, made mud pies and played on the adventure playground, nicknamed the “anarchy zone.” When I moved back to New York City, I took a job as a playworker at The Yard on Governors Island, a junkyard playground, where there are only three rules:

No adults allowed (except playworkers)

Don’t hurt yourself

Don’t hurt anyone else

I was both intrigued and skeptical. The Children’s Garden operated by the same philosophy, that play should be child led, but this place gave children tools like hammers and saws. I wondered how the hell no one sawed their thumb off?! As it turns out, children do a wonderful job of regulating themselves and their safety when given sincere trust.

A playworker’s job is to judge risk vs hazard. They encourage the children to engage in risky play, like on a seesaw made from plywood and an old tire. Risky play helps to develop skills related to problem solving, self advocacy and resilience. At the same time, playworkers keep the environment safe from hazards. They are constantly scanning for things that might cause emotional or physical harm, like peer pressure or pointy nails.

The playground was a safe space to explore risk. The more time I spent there, the more I realized that safety and freedom are interconnected: In order to feel free, you must also feel safe. In order to feel safe, you must also feel free.

I started to bring the philosophy of the playground into my personal life. I started to take more risks. I was trading in my perfectionistic behaviors for playful experimentation. I stopped cooking from recipes and started improvising in the kitchen. I stopped shaving my legs and started shaving my head. I took myself out on solo adventures to museums and restaurants and concerts.

I changed my first, middle and last name. Why not? I chose Lee as my first name, which means meadow, and Field as my last name. I wanted space to frolick: long grass, honeybees and wildflowers. I took Star as my middle name, a glimmer of light amid the darkness.

As I started to liberate my own inner child, I became increasingly aware of the ways society seeks to keep us cut off from our childlike nature. To be in touch with our inner child is to be kind hearted, free spirited and courageous. The white supremacist heteropatriarchy that we live under would rather us closed-off, fearful and obedient.

I see an important distinction here: Oppressive forces want us small minded (fearful, inferior) while liberation work wants us young at heart (optimistic, hopeful).

18 years later, the psychic reading from the birthday party has proven true. The gendered aspect of the reading is only helpful to me for naming these different parts.

The old lady has revealed herself not as a wise woman but as my inner critic. She is shaped by systems of oppression that rely on fear. She speaks unkind words to me and floods my mind with undue worry in a misguided attempt at safety.

The little boy has revealed himself not as a rambunctious trickster but as my inner child. He is in touch with his divine childlike nature. He encourages me to try new things, to remain curious and to move past limitation.

The Six of Cups invites us to be more like the little boy: to play and to love as a means of liberating ourselves and each other.